Narratives are the collection of stories that help us make sense of the world. They shape and determine what/who we notice or ignore, what/who we think is legitimate or not, and what we believe is possible or not.

A narrative isn’t just one story, it is a whole system made of frames and stories that connect around a central idea or belief. When those stories get repeated again and again, the narrative becomes familiar, powerful, and we often accept it as truth and reality.

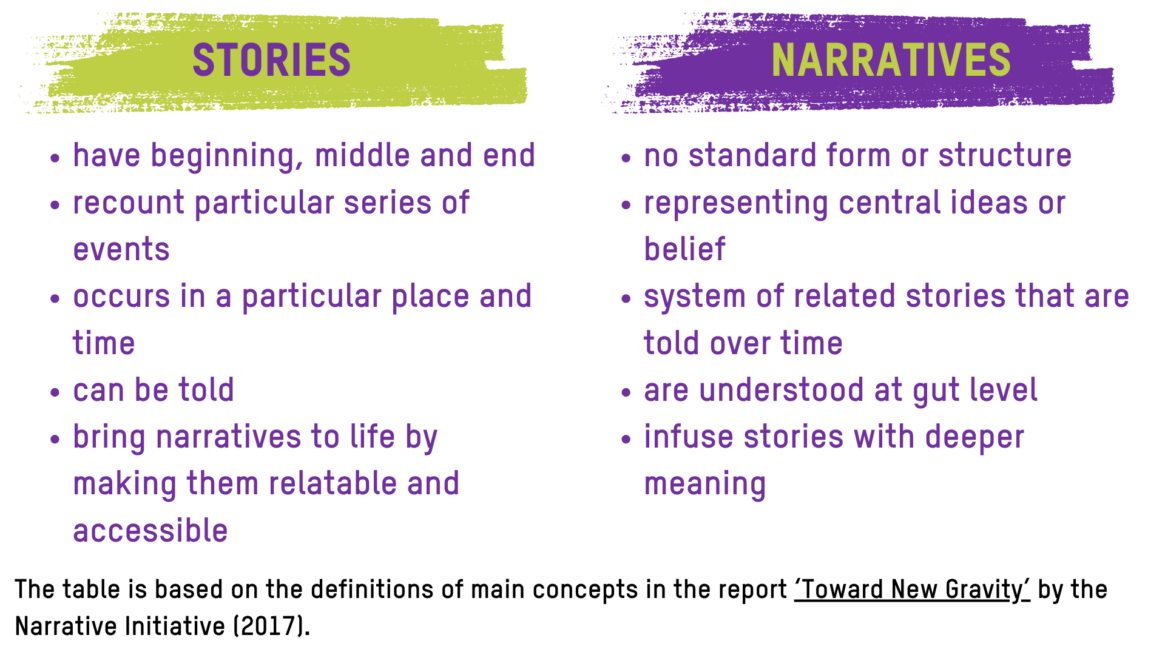

A helpful way to picture it comes from Narrative Initiative:

“What tiles are to mosaics, stories are to narratives. Stories bring narratives to life by making them relatable and accessible, while narratives infuse stories with deeper meaning”

In that sense, narratives are tools of power and are used by prevailing actors and structures (from the political, economic and religious realms) to entrench power dynamics. Dominant narratives influence which issues are seen as urgent and which voices seem credible in the public sphere.

Dominant narratives hold the current system of power in place. They can make harmful actions or inactions by those in power seem inevitable, normal, legitimate, or even beneficial. Dominant narratives can limit our range of actions and our ideas of what is possible, both individually and collectively.

For example, in many contexts, civil society organisations (CSOs) and human rights organisations are criticized as being out of touch, driven by foreign interests, or wasteful with money. This criticism, loudly repeated and often amplified by social media, has fueled anger and resentment among the public, and has justified limiting the space for CSOs to do their work. This is how a dominant narrative can justify backlash, repression and shrinking civic space.

Alternative narratives break away from dominant narratives prevalent in society. They often come from people and communities who are sidelined or not in positions of power. As a result, they introduce perspectives that are usually overlooked and can widen our imagination about what is possible. They help question assumptions and stereotypes, challenge power structures, and highlight different priorities and values. When they gain momentum, they open up new paths for collective action and change.

A good illustration comes from JustLabs, a collective of 12 human rights organisations working across different countries. In face of hostile narratives about civil society, JustLabs focused on three alternative narratives that highlight different values and priorities: community, culture and cooperation. These alternative narratives offer a different lens and open new space for engagement, trust and action.

You can find narratives on any topic: climate change, gender, youth leadership, civil society, digital rights…and many more. A healthy civic space relies on having many ideas and many voices discussing these topics. And because every person brings their own worldview and lived experiences, the same narrative can be interpreted and perceived in wildly different ways. This diversity is a reminder that narratives are deeply personal.

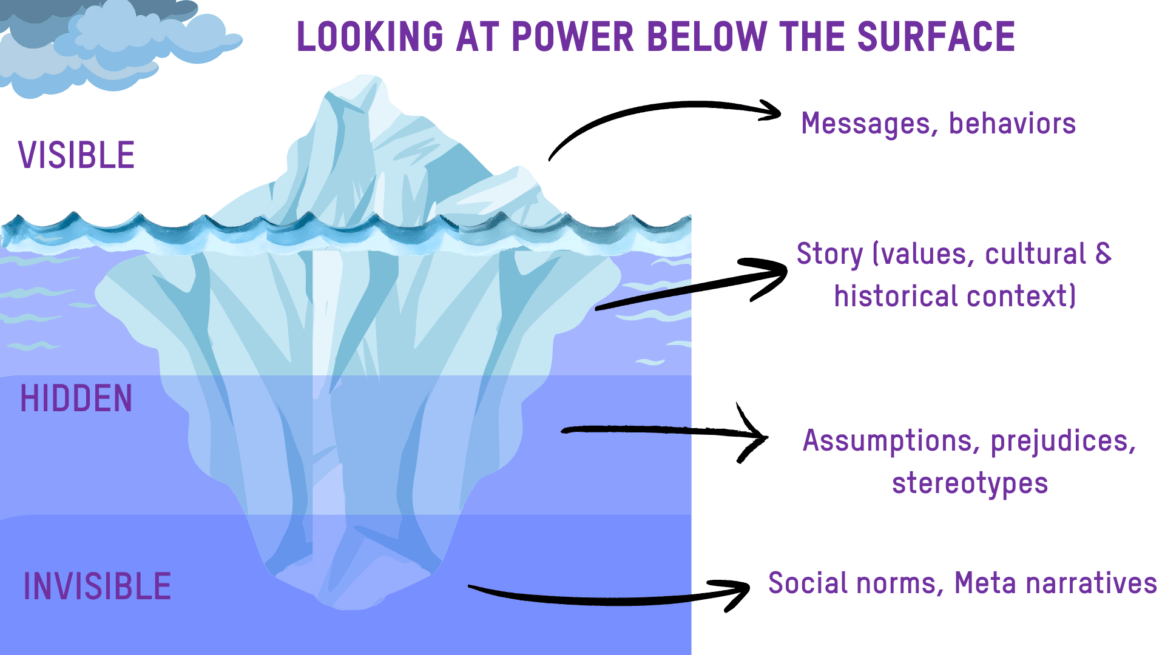

Narratives are made up of many layers of meaning. But what we notice and usually recognise is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’- behaviors, messages, slogans that we see or hear. Beneath the surface, it is connected to deeply held and shared social norms and values, history and culture. Because they are often invisible, they can be harder to see, and even harder to shift.

Figure 1: The visible and invisible layers composing narratives